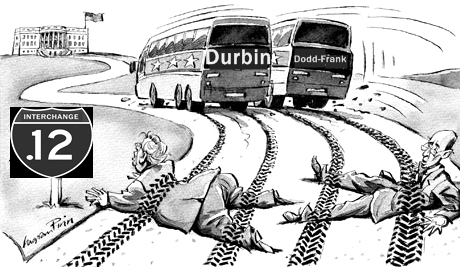

The Durban Agreement and the Durbin Amendment have one thing in common. They are both working towards an ideal climate. The former regulates carbon emissions and hopes to reach a global climate agreement; the latter regulates interchange fees and hopes for a universal agreement on a fair climate for financial services.

Signed into Law on July 21, 2010, the Durbin Amendment to the Dodd-Frank Act, introduced by Sen. Richard J. Durbin, ignited a spark of unrest among varied stakeholders of the financial services industry. The amendment was slammed on the Dodd Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act at the eleventh hour in an attempt to move a step closer to the retailers’ legislative agenda. This year, the amendment completes its third year.

Signed into Law on July 21, 2010, the Durbin Amendment to the Dodd-Frank Act, introduced by Sen. Richard J. Durbin, ignited a spark of unrest among varied stakeholders of the financial services industry. The amendment was slammed on the Dodd Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act at the eleventh hour in an attempt to move a step closer to the retailers’ legislative agenda. This year, the amendment completes its third year.

Through this amendment, the Federal Reserve decided to reduce the fees that merchants pay banks when consumers use their debit cards. It was entitled as ‘Reasonable Fees and Rules for Payment Card Transaction’ and prescribed standards for ‘reasonable’ interchange fees, that are payable to certain debit card issuers.

In a statement that Wednesday morning in 2010, Sen. Durbin said, “Small businesses and their customers will be able to keep more of their own money.” He added, “Making sure small businesses can grow and prosper is vital to putting our country back on solid economic footing.”

In essence, the Amendment pits two critical players in the financial battlefield against each other – businesses and banks.

Payment services companies, the two predominant players being – Visa and MasterCard, set the interchange fees, but financial institutions that issue the debit cards reap most of the gains generated from the fees. American businesses, as a result, are forced to pay high debit interchange fees, reducing their profit margins and leading to higher retail prices for consumers.

Payments service companies only earn a percentage of each transaction they facilitate but the more debit cards are issued, the more profits they earn. Here, a good bait for the payments services to throw at financial institutions is to offer the highest interchange fees, since it will bring the highest return for banks.

Note here, that by setting a higher interchange fee, the purpose of the payments service companies is to win banks, not necessarily consumers.

This partly explains the highly uncompetitive payments services market where 80% of electronic transactions are dominated by Visa and MasterCard. National electronic service companies like PayPal and Discover have made significant attempts to break through this monopoly, but it continues to remain a work-in-progress.

Section 1075 of the Dodd-Frank Act, which is the Durbin Amendment, added a new section 920 to the Electronic Fund Transfer Act (EFTA). The new section seeks to define an amount of interchange fee that is reasonable and proportional to the cost incurred by the issuer. It charges the Fed with the duty to oversee the debit interchange rates are directly related to the debit transaction costs.

In its most recent study, the Fed capped debit interchange fees for large banks at twelve cents, substantially lower than the national average of 44 cents per debit transaction. This is likely to result in a loss of billions for American banks.

There is some solace however for banks and credit unions holding under 10 billion dollars in consolidated assets. The Durbin Amendment exempts them. This exemption is viewed by some as a political act to go after large banks that receive billions of dollars of taxpayer’s money.

Besides cracking down on big banks, the amendment also intends to infuse more competition into the electronic payments services industry. The underlying goal being that more competition will lead to lower interchange fees. The Amendment requires issuers to issue debit cards of atleast two unaffiliated networks. Unlike the exemption on interchange fees, there is no exemption on this for small banks and credit unions.

Sandwiched between the payment services companies and the big banks, the merchants have struggled over the years to raise their profit margins from retail sales. The Durbin Amendment took recognition of that and explicitly allowed merchants to offer discounted prices for certain types of financial transactions and even refuse to accept debit cards for small purchases. This is a welcome relief for small business, that most often suffer the impact of interchange fees, due to the lack of economies of scale.

Meanwhile, the fierce fight continues between the banking institutions and businesses.

Banks accuse the Durbin Amendment for allowing a way for avaricious businesses to earn more profit at the expense of community banks and consumers; businesses argue and charge the amendment for allowing Wall Street executives to earn more profit at the cost of small businesses and consumers.

In a Senate Banking Committee, Sheila Blair, Chairman at Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, remarked, “the likelihood of this hurting community banks and requiring them to increase the fees they charge for accounts is much greater than any benefit retail consumers may get.”

The question looms large: Is this Amendment really just a mere transfer of wallets from big bankers to big businessmen?

On May 23, 2013, the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve released an analytical study on the Impact of Regulation II on Small Debit Card Issuers. This study draws on Regulation II of the Durbin Amendment that makes it mandatory for every debit card issuer, irrespective of size, to have at least two unaffiliated networks on every debit card.

While small debit card issuers are exempt from the Durbin amendment on interchange fees, they are not exempt from network exclusivity. The point of contention here is that networks do not establish separate interchange fee for exempt issuers, thus undermining the effectiveness of such an exemption.

The study highlights three issues in particular. One is the issue of having separate interchange fee schedules for exempt and covered issuers. It was observed in 2012, that networks provided a higher average interchange fee to exempt issuers than non-exempt issuers. The second issue at hand looks at the change in exempt-issuer interchange fees since the implementation of interchange fee standard on non-exempt issuers. It highlights that in 2009, the average interchange fee for all issuers was 43 cents. “For the first three quarters of 2011, before the interchange fee standard took effect, exempt issuers received an average of 44 cents per debit card transaction. The average interchange fee per transaction received by exempt issuers has returned to the 2009 level of 43 cents since the implementation of the interchange fee standard”, the study reports.

The third issue relates to changes in exempt-issuers’ interchange revenues. In 2012, the exempt issuers received $7.4 billion in total debit card interchange revenue, compared with approximately $5.3 billion in debit card interchange revenue in 2009, according to the study.

Some of the other issues pointed out by the study are the evidence of discrimination against cards issued by exempt issuers and the cost to small issuers of adding a second unaffiliated network. While the Fed conducted a survey with the community commercial banks, credit unions and thrifts, the responses were voluntary and conditioned on the willingness and ability of participants. Hence they cannot be considered representative of the overall experience of small issuers but they do highlight that the regulation has had potential effects on small issuers.

To seek further clarity of the impact of the amendment on banks, issuers and consumers, several economists are still conducting research. According to one such study that is still a work-in-progress, it has been observed that the overall interchange reduction increased the market capitalization of merchants by a far greater margin than it decreased the market capitalization of banks. It was also noted that the cost to merchants for taking payments on debit cards declined while the effective cost to issuers for providing debit card services to consumers increased by a corresponding amount.

The critical question is whether consumers gained more from cost savings passed on by merchants in the form of lower prices and better services, than what they lost from cost increases passed on by banks, in the form of higher prices or less service. Some economists estimate that the consumers lost more on the bank side than they gained on the merchant side.

In the fourth quarter of Economic Review 2012, Fumiko Hayashi in his report titled, ‘The New Debit Card Regulations’, concluded that the regulatory and legal changes imposed on the debit card industry had diverse effects, with several distinct implications for market competition among card networks and card-issuing banks.

“Most card networks have set two separate interchange fee schedules: one for regulated banks, conforming to the new caps on interchange fees for those banks, and a separate one for exempt banks. Although the card networks can still set interchange fees as they see fit for exempt banks, the regulatory and legal changes have created new incentives that exert downward pressure even on the exempt banks’ fees”, Hayashi revealed.

On observing the changes in market shares among debit card networks over the past two years, competition had risen among debit card networks. A good example of increased competition among the network for merchants is the decline of Visa’s market share, especially in the PIN debit card market.

“Regulated banks have seen their interchange fee revenues fall while exempt banks’ revenues have remained roughly the same, on average. Regulated banks’ new incentives are likely to drive marked changes in their product promotion efforts as they encourage customers to shift from signature debit to PIN debit and from debit card use to other payment methods”, the report stated.

Among some anticipated consequences is the propensity of competition to rise between the regulated and exempt banks and within the exempt group. The nature of competition within the regulated banks has changed as a result of the amendment but whether that is likely to rise is yet to be established. According to Hayashi, “Regulated banks may no longer seek to attract customers by offering rewards, but they now have more incentive to compete for customers by reducing or eliminating the fees associated with checking accounts and debit cards”.

By raising the level of competition among card networks and by shrinking the fees charged to merchants, the regulators seem satisfied with their interventions. What unnerving for the rest of us is the unintended consequences.